- Home

- Lovett, Charlie

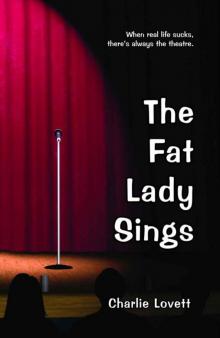

The Fat Lady Sings Page 2

The Fat Lady Sings Read online

Page 2

“You better believe it, boys,” I say, jiggling for the benefit of some quartet of jocks I’ve never seen before and will probably never see again.

They peel out with a squeal of tires and shrieks of laughter, but I know they enjoyed the view. Or I hope they did.

I hate those moments — when you think you’re all cool and too good to be bothered by some cretins, but underneath it feels like they just ripped your heart out and emptied a saltshaker into the hole in your chest.

Scene 2

Cameron started movie nights at his house last year when his parents got Netflix. It started out as fun way to watch classic movies, because all that ever plays at our pathetic excuse for a local multiplex is mediocre rom-coms starring the anorexic starlet of the month and slasher flicks so full of fake blood they’re probably diving up the price of corn syrup. So we went through Citizen Kane and Casablanca and a few Hitchcocks, and then Elliot broke up with his girlfriend and movie night went from classic Hollywood education to teenage angst and emotional crisis.

There was Cameron coming out — to us, not to his parents, of course — (Rocky Horror Picture Show), me failing a math exam (A Beautiful Mind), Elliot losing the student council election (Mr. Smith Goes to Washington), Suzanne’s parents separating (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf), and a few dozen other crash and burn moments punctuated by the greatest Hollywood has to offer. Turns out, some good friends and MGM work a lot better than the suicide hotline.

Dad and Karl won’t let me go to Cameron’s on a school night, even if I give them the old “But Cameron’s gay — he’ll be a good influence,” or tell them we’re watching a Judy Garland film. But this week I’m with Mom, so it’ll be no problem.

One thing you should probably know about my mom — she took the whole “my husband dumped me in the late stages of my pregnancy to be with the male gynecologist” thing pretty hard. I mean, who wouldn’t, right? I guess Dad thought he was doing the right thing by not leading her on or whatever, but he probably should have at least waited until after the birth. Then again, I’d abandon my family in a second if it meant I could be with Roger Morton. Anyway, my mom’s pre-partum depression gave way to pretty serious post-partum depression which she never really got over, even though she medicates nightly with multiple doses of Jim Beam.

She’s nice during the day — like when we go shopping together on Saturday afternoons sometimes (OK, twice) — and she holds down a job as a cashier at Target, but by the time dinner rolls around she’s more interested in the bottle than in me. So on the one hand, my mom’s an alcoholic who ignores me in favor of reality TV, the local beer joint, and the occasional drunken hook-up; but on the other hand, I can do pretty much whatever I want on a school night. Always look on the bright side, right?

So I grab a frozen dinner while mom is zombied out in front of Inside Edition, then get my bike out of the garage and head to Cameron’s.

That’s right, the fat kid on a bike. Shocked? I know what you were thinking — fat and lazy, right? Nope. I’m a drama jock; we’re a rare breed, but we do exist. I do plays and play a varsity sport. I know, surprise, right? And no, I’m not a sumo wrestler. I play field hockey. And I don’t just play for fun and to get out of gym class — I’m good. I’ve started on varsity for two seasons now, and we were undefeated last fall.

Something about having a stick in my hand brings out the animal in me. Miss O’Brien, who in addition to being the college counselor is also our field hockey coach, is always lecturing us about being more aggressive. “Except you, Agatha,” she says, “you’re aggressive enough.” Damn right.

So I play field hockey, I work out twice a week in the off season, and I was at every dance rehearsal for West Side Story this summer. Nobody who makes it through three straight hours of “America” on a Saturday afternoon in June when the air conditioner is broken is lazy. Crazy maybe, but not lazy! Plus, since Dad won’t buy me a car, I ride my bike to Cameron’s and the mall, and walk to school, because there is no way I’d let those goons see my fat ass on a bike.

So now you’re thinking “glutton,” and honestly, I like ice cream and pizza as much as the next person, but not any more than the next person, and a lot less than Cameron and Elliot, who can each eat enough to feed a small Albanian village and still look like an ad for famine relief. So call me big-boned or well-endowed or voluptuous or any of those other euphemisms — even call me fat. I embrace “fat.” I am fat.

Just don’t call me overweight — because if I’m “overweight,” then that means there is some ideal weight that I should be, and I’m not buying that one. I exercise, I eat reasonably healthy food, and I’m fat. So when somebody tells me “you should lose weight,” I want to say, “you should become Asian.” It’s who I am, OK? Deal with it.

Cameron lives in the same neighborhood as Dad and Karl — in fact, I have to take the long way around to avoid their house, just in case Karl is out front working on his flowers. Cameron’s house has a garage apartment that he’s converted into a screening room/editing suite — did I mention he wants to be a filmmaker? He’s already applied to USC for next year.

When I make my entrance, Elliot and Suzanne are already there, Elliot slouched on the couch like he owns the place and Suzanne with her head behind the TV fiddling with some wires.

“Technical difficulties,” says Elliot, nodding towards Suzanne.

Suzanne has this reputation for never going outside in the daytime and some of the kids at school call her a vampire (she is a little goth, but hey, anybody who works backstage as much as she does accumulates some black clothes, OK), but she can fix anything. She’s the one who set up all of Elliot’s equipment in the first place.

“Hi, Suzanne,” I say.

“How was the audition?” she asks. “I was working on the sound board so I missed it.” She says all this without removing her head from behind the TV.

“She was magnificent,” says Elliot, before I can open my mouth. “Stupendous. I give her five stars.”

“Yeah,” I say, plopping down on the couch, “but how many stars will Parkinson give me?”

“Roger liked it,” says Elliot, nonchalantly.

“Are you kidding,” I say. “You better not be messing with me.” I grab Elliot’s arm and twist it behind his back. “Are you messing with me?”

“I don’t think she wants you to mess with her,” says Suzanne, her smile finally appearing from the darkness.

“I’m not messing with you,” screams Elliot. “Let go!”

So I let go. “What did he say?” I ask, trying without success to will my heart into not racing.

“He said he’d never connected with anybody on stage like that before.”

“Are you serious!” I say. “Oh my God.” I hug a pillow to my chest and have this blinding vision of Roger leaning over to kiss me.

“He didn’t say he loved you, OK. He just said it was a good audition. I knew I shouldn’t have said anything.”

“Of course you should have,” I say, completely ignoring the “he doesn’t love you” part of what Elliot said. “What else did he tell you?” I ask, as Cameron comes in with a giant bowl of popcorn.

“He told me Cynthia Pirelli looked really hot,” says Elliot.

There’s an awkward silence and then I smack him with the pillow as hard as I can (which is pretty hard) and try to swallow the tears that are suddenly burning to get out.

“Now why would you say a thing like that?” says Cameron, throwing a handful of popcorn at Elliot.

“Sorry,” says Elliot, suddenly contrite. He reaches out towards me, but I pull away. “I just don’t want you to get any illusions about Roger Morton. And I wanted you to know it was a great audition and he thought so, too.”

“I don’t have any illusions about Roger,” I spit at Elliot. But of course I do.

“How did your singing audition go?” asks Suzanne, who is as good at changing the subject as she is at changing the wiring on Elliot’s video system.

“Yeah.”

“Well, the way I sang they probably wished it was over.”

“But Parkinson has heard you sing before,” says Cameron. “He cast you in Godspell.”

“Yeah, but not with any solos,” I say. “Anyhow, how do you think Carol Channing’s singing audition went?”

“She wasn’t exactly a crooner,” says Elliot, his eyes searching mine for forgiveness. “Dolly’s a Rex Harrison part anyway — it doesn’t need a good singer.”

And Cameron immediately starts in on his impression of Rex Harrison singing “Why Can’t a Woman Be More Like a Man,” which is pretty hilarious when sung by a gay male. We all burst out laughing and I wink at Elliot and we both know that everything’s OK.

And there we are, the four of us, just like we’ve been since junior high.

We met at the auditions for Guys and Dolls, Junior before Cameron knew he was gay or Suzanne decided her talents lay backstage, but not before Elliot was cool and I was fat. We just happened to plop down next to each other and something clicked — like we were the perfect cast in a four-man show. We started eating lunch together and then going to movies together and then doing almost everything together. It was strange after so many years of resenting the cliques that had excluded me to suddenly be a part of my own and to have the pleasure of excluding others — not that people were scrambling to hang out with us, but at least it felt exclusive.

Suzanne is the quietest — totally at home with a wrench in her hand, dangling thirty feet above the stage adjusting a light, but never quite comfortable making conversation, even among friends. I remember one afternoon we were hanging out at Cameron’s, just joking and laughing and Suzanne didn’t say a thing all day and when we left, just before she got in her car, she turned and gave me a hug and said, “That was the best afternoon ever!” That’s Suzanne — always in the wings and loving it.

Cameron, needless to say, is the flamboyant one. He has a wicked sense of humor, and can sing pretty much every song ever written for Broadway, but the degree to which he lets people see all that — the degree to which he’s out of the closet — varies widely depending on the company. With us he’ll practically put on a drag show, sans the actual drag; with his parents he’s the good, studious, son who just can’t seem to find a girlfriend; with everyone else, it’s something in between.

Elliot’s the one of the four of us who actually has other friends, too. He’s as comfortable with football players as he is with drama geeks. He’s also the most relaxed person I’ve ever seen on stage. He got the male lead in everything until Roger Morton started auditioning last winter — but since Elliot was the one who convinced Roger to try acting, it didn’t bother him that he was suddenly playing second fiddle. To this day I’m not sure if Elliot invited Roger into the theatre because he genuinely thought he’d like it, or because he knew I’d had a crush on Roger since the third grade at James K. Polk Elementary School. Either way, I’m OK with it. And I’m very OK sliding back into the couch to watch a movie with my three best friends and forgetting about the outside world for a couple of hours.

It turns out Sunset Boulevard is all about this washed up silent movie actress who nobody needs anymore — possibly not the best karma for a senior who’s up for the part of her life against Cynthia C-cup, but at least we weren’t watching All About Eve.

After the film I decide maybe it’s OK to talk about my audition again, as long as I make it clear that it’s just the audition I’m talking about.

“So did anybody else sense that connection during my audition today?” I say, as nonchalantly as I can.

“I mean, forget it was Roger. It’s just that something happened in that audition that has never happened to me on stage before, and as an actress I’m interested in figuring out what it was.”

“I saw it,” says Cameron, “and you’re right, there was a connection that you don’t usually see. Like for a few seconds you weren’t actors, but you actually were Dolly and Horace.”

“Sometimes it just happens,” says Suzanne. “I saw the same thing when Pam French was reading for Madge in Picnic. But I never saw it again after the audition, not even on closing night.”

“Yeah, well that’s what happens when you cast a gummy bear,” says Cameron. That’s what he calls someone who auditions well but then never gets any better, or even gets worse. “Because when I see a bag of gummy bears,” he explained one time, “they look like a really good idea, but the more I eat, the more I regret it.”

“It doesn’t ‘just happen’ if you know what you’re doing,” says Elliot, back on the subject of the connection Roger and I made. “Read your Stanislavski. In the beginning of An Actor Prepares it happens almost by accident — that total surrender of actor to character — but the rest of the book is figuring out how to do it on purpose. ‘Look for what is fine in art, and try to understand it.’”

Leave it to Elliot to break up the party by quoting Stanislavski. It’s no wonder he got into Duke early decision.

Scene 3

I’ve done this a thousand times before — OK, maybe not a thousand, more like ten, but still, I am used to this. That’s what I tell myself. Checking the cast list is just one more thing I have to do before math. When I was a freshman I would rush up to the theatre department bulletin board and elbow my way through the crowd, past the sobbing rejects and the shrieking leads and frantically search for my name. But I’m not a freshman anymore. However I feel on the inside (like I’m gonna throw up, in case you’re wondering), I shall be cool on the outside. I wait calmly behind the chaos until the crowd notices me and slowly begins to part; and they have to part quite a bit because, as you know, my hips require some respect. But they do part — they step back almost in awe, which I figure is a good sign because it probably means I got cast as Dolly and they are intimidated by me already. I glide up to the board all stately, like the Titanic or something, and pick up the pencil that’s hanging there by a piece of string so I can initial my name next to the words “Dolly Levi.”

Only it’s not my name. It’s Cynthia Pirelli.

And now my stomach is sinking like a rock and I’m thinking that the Titanic was sooo not the right metaphor and I have to keep my super cool exterior because being the fat kid in front of everybody is bad enough without being the devastated fat kid in front of everybody, and then I see my name next to the word “Townsperson.”

Townsperson! My character doesn’t even have a name.

Every actor but me has initialed their parts, and now everybody is standing there looking at me, waiting to see what I’ll do. They all know I didn’t get the lead, and probably most of them think I should have gotten the lead, but all they can think now is “What’s she gonna do?”

You can feel the anticipation — if people were sitting down, they’d be on the edge of their seats. And for a second my stomach stops sinking and I think, I’m on stage. I’m the star of the most dramatic moment of the day. I’ve got everyone holding their breath and leaning every so slightly forward to watch me. It’s kind of powerful, if you think about it.

So slowly, with great grace and dignity, trying my best to channel Katherine Hepburn, I step slightly to the side so everyone else can lean in and watch as I write, next to my name, “No F-ing way.”

I write it just like that, so they can’t get me for profanity. “No F-ing way,” and this little gasp goes up from my audience.

Oh, I play the tragic heroine with aplomb. And then I gently set the pencil down and glide back through the crowd and down the hall, and when I am about ten feet away, I hear it.

I was expecting giggles and that gossipy sound that usually permeates the halls, but instead I hear someone clapping. And then suddenly, like someone had just turned up the volume, the whole hall is full of applause.

I walk a few feet further, then turn, and curtsey elegantly to all the drama geeks standing there by that profane c

ast list and applauding me. For the end of my life, it’s a pretty good moment. Keeps me from crying until I get around the corner, at least.

Third period math is the worst fifty minutes of my life. Not only do I not have a clue what Mr. Donahue is talking about, but math is the one class I share with Cynthia Pirelli, who is officially the last person in the solar system I want to see right now.

She’s covered up today, wearing a big loose T-shirt, and she keeps staring over at me with this pathetic look on her face and trying to mouth “I’m sorry,” and stuff like that, but I won’t look at her. I mean, not directly — I have great peripheral vision, so I know what’s going on. She wants me to forgive her for stealing my part, but I’m not gonna do it. If it bothers her so much, why did she accept the role? Why did she even audition?

Of course everybody else in class knows what’s going on and they’re watching us like we’re like something on Animal Planet, so finally, when we’re supposed to be solving a problem in the workbook, I go up to Mr. Donahue and tell him I’m having “female issues,” which means he’ll write me a pass for the moon as long as he doesn’t have to hear any details. So I guess technically it’s the worst thirty-five minutes of my life. Then I go and hide in the props shed.

I stop by the supply room to collect a box of tissues. When she sees how red my face is, Miss Overman doesn’t even ask me why I need them. “Allergies,” I say, sniffing and willing myself not to cry again until I’m safely hidden away, face down on a couch that’s musty enough that if I did have allergies it would probably kill me. Then I have a good long sob.

Even though my heart is broken and my life is over, it actually feels fantastic — not quite good enough to make it worth having your heart broken, but close. I think it’s endorphins or something, but have you ever noticed how good a cry can make you feel? Not that “catch it in your throat and try to squeeze it shut before it starts because there are people around” sort of cry, but the “I’m all alone and I can release everything I’ve been holding inside of me” cry.

The Fat Lady Sings

The Fat Lady Sings