- Home

- Lovett, Charlie

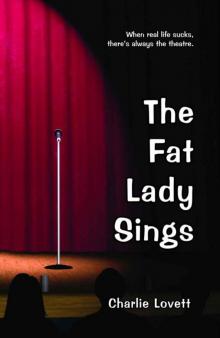

The Fat Lady Sings

The Fat Lady Sings Read online

Table of Contents

The Fat Lady Sings

Act I

Scene 1

Scene 2

Scene 3

Scene 4

Scene 5

Scene 6

Act II

Scene 1

Scene 2

Scene 3

Scene 4

Scene 5

Act III

Scene 1

Scene 2

Scene 3

Scene 4

Scene 5

Act IV

Scene 1

Scene 2

Scene 3

Scene 4

Also by Charlie Lovett:

About the Author

About Pearlsong Press

The Fat Lady Sings

Charlie Lovett

Pearlsong Press

P.O. Box 58065

Nashville, TN 37205

www.pearlsong.com | www.pearlsongpress.com

Copyright 2011 Charlie Lovett

www.charlielovett.com

Ebook ISBN: 9781597190312

Trade paperback ISBN: 9781597190305

Book & cover design by Zelda Pudding with mic & stage art copyright sarah5

Also by Charlie Lovett: Books

Love, Ruth: A Son’s Memoir

Sparrow Through the Hall

Lewis Carroll’s Alice

Alice on Stage

Lewis Carroll’s England

Lewis Carroll and the Press

Lewis Carroll Among His Books

Everybody’s Guide to Book Collecting

Olympic Marathon

J.K. Rowling

Onward and Upward

The Program

Plays

Twinderella

Woing Wed Widing Hood

Snew White

A Hairy Tale

Porridgegate

Romeo and Winifred

Omelette: Chef of Denmark

Unwrapped

A Nose for the News

Supercomics

Little Miss Gingergbread

The Emperor’s Birthday Suit

A Super Groovy Night’s Dream

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lovett, Charles C.

The fat lady sings / Charlie Lovett.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-59719030-5 (original trade pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978159719-031-2 (ebook)

I. Title.

PZ7.L95938Fat 2011

[Fic] — dc22

2010052015

To Sandra

Who Took A Chance on Me

Act I

Scene 1

Cynthia Pirelli’s boobs are sooooo fake. I’m not saying they aren’t gorgeous — who could miss that fact when she’s wearing a top cut so low it’s a wonder her naval ring doesn’t get caught in the neckline. Whoever her plastic surgeon is does great work. But they’re still fake. How do I know? How can anybody not know? Little Miss A-cup is “out sick” for the week after her eighteenth and when she comes back she’s busting out all over. What was she sick with? Boob mumps?

“What do you want for your eighteenth, Cynthia honey?”

“Boobs, stepdaddy who’s desperately trying to buy my affection.”

“Anything for you, pumpkin.”

What a charming domestic drama. Makes me want to puke.

You probably want to know why I even care about Cynthia Pirelli’s boobs. What about you, Aggie, I hear you saying. You have big boobs, too. True — but I also have big arms, a big neck, big thighs, and a big butt. No, let me rephrase that, a huge butt. You see, I’m fat. Not pudgy or robust or big-boned or any of the other things the “nice” people try to call you when you’re looking in the mirror or dreading the showers after gym class. I’m fat, plain and simple.

Fat. On good days I embrace that word; on good days if someone calls me fat I slap my butt and say, “You bet, and proud of every pound!” On good days every jiggle makes me giggle and I love who I am. And then there are the bad days. On bad days “fat” is a four-letter word; “fat” is everything that is wrong with me and this school and the world. On bad days, fat sucks!

There are two other really annoying things about Cynthia Pirelli.

First of all, she’s good at math. Not just so-so, “she could skate along with no effort and get a B” good, but “she could teach the class” good. This is a problem because I suck at math, but I’m taking AP Calculus because Miss O’Brien, the college counselor, says it will “look good on my applications” (am I ever sick of that phrase).

“If you want to go top tier, you’ve got to have AP Calculus,” she told me. I don’t care what tier I end up in; I just want to go someplace with an amazing theatre program, but I’m not taking any chances, so I signed up for the stupid class.

So now I’m stuck in it, and the problem is that Cynthia Pirelli, in spite of her fake boobs, is really nice about helping me, even if I text her at two o’clock in the morning when I’m brain fried and don’t know my integrals from my differentials. I know this might not seem like a problem, but because of the boobs and the last thing I’m going to tell you, I would very much like to hate Cynthia Pirelli. Her helping me out with calculus, and being so nice about it, makes that hard.

But not impossible.

The last thing you need to know is that Cynthia Pirelli can’t act. I realize there’s nothing particularly hate-worthy about that. Plenty of perfectly nice people can’t act. My stepdad, Karl, for instance, and he’s a gay man, so you’d think —

The problem is not simply that Cynthia can’t act. It’s that in spite of that fact, in spite of the fact that she’s probably never been in a play in her life, in spite of the fact that I’ve been to every audition of my high school career and spent three years in the chorus and playing Messenger Number Three to reach this moment, my moment, Cynthia is, at this very instant, standing on stage auditioning for the part of Dolly Levi — a role I have been preparing for since birth. And she’s reading opposite Roger Morton. Roger Morton! And neither Roger nor Mr. Parkinson seem to notice that she can’t act because they’re staring at her fresh-out-of-the-oven boobs. I swear Mr. Parkinson is actually drooling. Drooling! I can see it shining in the stage lights like a beacon of moronosity. OK, that’s probably not a word, but you get my point.

“Couldn’t act her way out of a wet paper bag with a sharpened stick,” says Cameron, leaning across my seat at the back of the auditorium. “Nice boobs, though.”

“They’re fake,” whispers Suzanne.

“Well, duh,” says Elliot, “But still — “

“You get what you pay for,” says Cameron, eyes on the cleavage.

I stab Cameron in the side with my elbow. What does he care about cleavage anyway?

Crap. Mr. Hart, my English teacher, says the first character I introduce in a story should be the protagonist, and here I am rattling on about Cynthia Pirelli’s boobs. Cynthia is not the protagonist. That would be me.

I’m Agatha Stockdale. Horrible name, right? Apparently my mom read these Agatha Christie mystery novels through the whole pregnancy and “just loved the name.” My dad wouldn’t fight her on it because he felt guilty about — well, you’ll see. So, Agatha. I mean, if you’re going to call me something old-fashioned, at least make it Hippolyta or Hermia or Beatrice — something Shakespearean, something theatrical. But Agatha? Ugh! To the less tactful students of Piedmont Country Day School, I’m known as Butterball, Crisco, and, in their least imaginative moments, just “the fat girl,” as in “shouldn’t there be a beeping noise — the fat girl is backing up.” To my friends, all three of them, I’m Aggie.

I’m an actress. I’m also a writer. It’s the only way I know to bring

a modicum of order to my crazy-ass life. Cameron once called me OCD, but I don’t touch parked cars or count how many times the letter “E” appears on a page, and God knows I’m not compulsively neat — anything but. I just write — blogs, e-mails, diaries, fan fiction, and occasionally even schoolwork. And sometimes, like when I’m trying to calm my nerves at an audition, I just write whatever I’m thinking.

Cameron has now been called on stage to read for Cornelius Hackl (gee, a gay Cornelius, that’ll make for a swell show), Suzanne has gone up to the booth to adjust the lights, and Elliot has moved to the front row (to get a better view of the cleavage miracles of modern science, I’m guessing), so I am sitting here alone writing while I wait for Mr. Parkinson to come to his senses and ask me to read for Dolly.

On the application to the Carnegie Mellon Summer Theatre Program, which I tragically did not get into, you had to write an essay explaining why you love the theatre (I guess if you’re willing to spend your summer in a dark room in Pittsburgh while everyone else is in the mountains or at the beach or schlepping across Europe, they assume you love the theatre).

For me, it started when I was eight years old spending the summer with my dad while my mom went “on vacation” (that’s what they told me. I found out later she was in a rehab center trying unsuccessfully to dry out). Most dads leave their wives for a hot young girl. Mine left for a hot young guy. I didn’t exactly get it at the time. I just thought “Uncle Karl” was this cool guy who lived with Dad to cut down on expenses or something. I was probably twelve before I started to catch on.

My parents’ marriage wasn’t one of those “gay guy marries his hag because they both want to have children and who else is he going to have them with,” or one of those “gay guy marries his hag because they promised that if they both made it to thirty without a serious relationship they’d get married and what the hell, tickets to Vegas are only $199.” No, my parents’ marriage was more like, “she’s never heard the word ‘hag’ and he went to a Catholic high school and got convinced he could ‘cure’ his gayness and he did ‘cure’ it until she got pregnant and they went to birthing class together and he met her gynecologist.” So I guess you could say that I introduced my dad to Karl.

I lead a split life — half the time with my dad and Karl in their restored historic house and half the time in a past-itsprime ranch with my mom. Dad offered to co-sign on a loan so she could buy a nicer place, but she said she wouldn’t take any of his F-ing charity. She said it just like that, “I won’t take any of his F-ing charity,” like not saying the whole word somehow made it better. Mom’s funny that way. She’ll rant and rave about Dad and say all sorts of awful things about him and then call him an F-ing S.O.B. I mean the word’s not what’s bad, right? It’s the meaning, and Mom can pack as much meaning into one “F” as anyone I know can put behind a whole word. Of course that’s all when she’s been drinking. When she’s sober she doesn’t talk much.

Anyway, falling in love with the theatre. I was eight and Karl was falling all over himself to try to be Mr. Super-Stepdad, so one Saturday night he took me to see his cousin play the role of Drake in a summer stock production of Annie.

Oh! My! God! I had never seen live theatre before — I mean my notion of entertainment up to that point was pretty much Reading Rainbow and SpongeBob. I was totally blown away. And on top of it being my first show and everything, I was feeling all abandoned and alone with Mom gone, and when that girl started singing about the sun coming out tomorrow, I completely lost it. I mean, she was me. I was Annie. Karl looked at me at the end of the number and saw that I was sobbing — tears literally falling off my chin. He tried to take me out to the lobby, but I refused to budge. I was hooked.

OK, yes, I realize now that it’s sappy and stupid and not exactly serious theatre, but I was eight, all right? It made an impression.

So Karl started taking me to the theatre. I’d sit through anything — Shakespeare, Tennessee Williams (which was no more sordid than my own family life), but my favorites were the musicals. And then a year later we saw Karl’s cousin play Ambrose Kemper in Hello, Dolly! Well, I might have felt like Annie was who I was, but Dolly was who I wanted to be. She was always confident and always smiling and always sure that everything would work out and that she would be the cause — I wanted that to be me. I wanted to be as sure of happiness as Dolly was. If I were Dolly, my parents would get back together. If I were Dolly I wouldn’t be fat. And if I were Dolly, the cute boy in the second row would like me. Because third grade was the first time I ever saw Roger Morton.

“Aggie! You’re up,” hisses Cameron. Crap! I have this way of disappearing into my thoughts, writing in my head or whatever, and the outside world kind of goes all fuzzy. Not a great idea at an audition, but I gather myself and pick up a script from the table and I take the stage — and I mean TAKE the stage. I’m channeling every grand dame I’ve ever seen on stage or screen, from Greta Garbo to Margaret Morgan from our local community theatre, who gets every old-lady part from Mrs. Potts to Mrs. Paroo. “Dignity,” I say to myself, “always dignity.”

Of course while I’m saying this my stomach is doing somersaults, because I’m about to read for Dolly freaking Levi, who is basically my idol, my mentor, and my inner child all at once.

I’ll bet Dolly Levi wouldn’t be nervous if she were the fattest girl in the senior class and auditioning for her dream role. But I am.

The stage lights are on so I’m completely blinded when I try to flash a knowing smile to Mr. Parkinson, a smile that says, “Now that the amateurs have finished, we can settle down to some real acting.” I have a sneaking feeling that it comes off looking like a maniacal grin, though.

“OK, Agatha, would you read Dolly, please. Roger, you stay up there and read Horace again.”

And the dream begins. Roger is Horace to my Dolly and all is right with the world. I flirt and flounce and Roger smiles and even touches my arm, just below the elbow, which makes me lose my place in the script for a second. Not that I need the script. I know Dolly by heart. I have since I was ten.

Roger and I have chemistry, I’m thinking as we near the end of the scene. We actually have chemistry. He responds to a talented actress, of course. Now he has something to play off of, not like when he was reading with Cynthia, who had all the emotional connection of a brick wall.

I drop my script to my side and look right into his eyes, and I think it throws him for a second, but then he goes with it. He steps into me and returns the stare and it’s electric. I know everyone in the theatre can feel it, and I know that I’m in for more of the same, because this is the most riveting audition ever. I can actually hear Cameron gasp as Roger reaches up and strokes my cheek, and for just a minute I think he’s going to kiss me, even though he’s not supposed to yet, but we are both completely lost in the characters and Roger has this look in his eyes like he’s discovered real acting for the first time and then, just when I think I might drown in those blue eyes, Mr. Parkinson says, “OK, thanks, Agatha. Nice reading. You can go. Roger, I’m going to need you for just a few more minutes if you don’t mind.”

And instantly the spell is broken and Roger is just Roger, not looking at me or even acknowledging my existence, and I’m just the fat girl wobbling down the stairs back out into the dimness of the auditorium. But theatre’s like that.

Cameron meets me in the hall outside the theatre — he’s standing there under the posters of Godspell and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Picnic with his arms crossed and a wicked grin on his face like something out of a gay version of the Abercrombie catalogue. “Hellooo Dolly,” he says with a grin.

I’m not so sure, but I put on my best Carol Channing voice and say, “Cornelius Hackl, how are you?”

“Ah, he’d never cast a gay Cornelius. It was fun, though. But you’re a shoo-in.”

“I’m not so sure,” I say. “He didn’t read me for very long.”

“He didn’t need to. You were fantastic. For a minute there, I thought

Roger Morton was actually in love with you.”

“And is that so very hard to believe?” I snap.

“Well, no,” says Cameron, suddenly dropping his pose and sounding contrite. “I’m sorry. It’s just that — “

“Don’t worry about it,” I say, throwing an arm around him. “It’s just been a long day, a stressful audition, and too much Cynthia Pirelli.”

“Amen to that. So — movie night tonight?”

“Might as well. I won’t be able to concentrate on homework. What’s playing?”

“Sunset Boulevard.”

“Sounds suitably dark,” I say, and I give Cameron a peck on the cheek and head for the parking lot.

It’s funny how simple that is, to give Cameron, a gay guy, a kiss on the cheek. How completely lacking in hidden meaning that gesture is. We’re just friends, no biggie. But if Roger Morton gave me a kiss on the cheek the Earth might very well stop spinning on its axis.

Piedmont Day is almost exactly equidistant between Mom’s and Dad’s houses, about two miles either way — so unless the weather sucks or someone offers me a ride, I usually walk home. Cameron has to make up a math quiz and Elliot and Suzanne are still at the auditions, so today I hoof it.

Walking home isn’t exactly a thrill, especially when the rest of school drives right by me and of course their first view is me from behind — which is NOT my good side, and a backpack with about fifty pounds of books isn’t exactly slimming. Usually I do my best to disappear, but it’s not easy when you’re my size. You try being inconspicuous when you’re the only person on the sidewalk and you’re a double-wide.

Dismissal time at Piedmont Day looks like a visit from the Vice President — black SUVs with tinted windows all over the place. Today I’m leaving at five, so the sports teams have all just let out and I hear an engine revving behind me and sense a car creeping up next to me. I stare straight ahead, which doesn’t usually work, but I do it anyway. I’m just not in the mood. The car is driving next to me for maybe thirty seconds when I hear the wolf whistle.

Now if there is anyone on the face of the Earth who knows the difference between an ironic wolf whistle and a genuine wolf whistle, it’s me, and this one is dripping with sarcasm. I should just let it go, but what with Cynthia Pirelli and auditions and everything, I can’t, so I muster my biggest, fakest smile, turn to them and pull down the neck of my T-shirt enough to give them a nice view of some cleavage.

The Fat Lady Sings

The Fat Lady Sings